Threats

Elasmobranchs have long generation times and low growth and reproductive rates, which make them extremely susceptible to overexploitation and prone to population decline. The majority of elasmobranch populations, especially large species, are not able to recover from the reduction in their population caused by fisheries as quickly as other fishes.

Overfishing

Overfishing is the unsustainable exploitation of aquatic resources, such as fish and other marine organisms, beyond their natural capacity to reproduce and replenish. When the rate of fishing exceeds the population's ability to grow, it leads to species depletion, disrupts ecological balance, and poses long-term harm to marine ecosystems. This issue is a significant threat to species targeted by the commercial fishing sector, with more than a third of global fish stocks currently overfished, impacting biodiversity and ecosystem stability. Additionally, over a third of sharks, rays, and chimaeras worldwide face threats from overfishing.

In India, there's a concerning trend in elasmobranch landings. The annual catch has steadily declined, dropping from approximately 33,500 tonnes in 1961 to around 25,900 tonnes in 2020, with some occasional increases. Gujarat and Maharashtra contribute significantly, accounting for 35% of the elasmobranch landings nationwide. An example of this shift can be observed in Thuthoor, Tamil Nadu, where local fishermen have diversified their practices from primarily targeting sharks to including other fish species.

An ICAR-CMFRI Rapid Stock Assessment (RSA) in 2015, comparing recent elasmobranch landings with historical data over 29 years, revealed declining or less abundant elasmobranch populations along most of the coast. Coastal shark species show signs of over-exploitation, and some have disappeared entirely, as noted by fishing communities.

The expansion of intense deep-sea fishing, especially in the southeastern Arabian Sea, is a growing concern. Deep-sea shark stocks in Indian fisheries have shown signs of collapse, with increased landings and decreasing individual sizes from 2002 to 2008. The species composition of landings has also changed compared to the 1980s and 1990s, a trend mirrored in Sri Lanka and the Maldives. With nearshore waters already heavily exploited and overfished, there's a growing likelihood of fisheries expanding into deeper waters. This progression raises further concerns about the state of marine resources in the region.

Fisheries bycatch

Overfishing is closely tied to bycatch – the capture of species other than the target species. Bycatch threatens marine megafauna, fishes and invertebrates through capture in non-selective fishing gear. In India, trawlers are responsible for large amounts of bycatch in general, including of elasmobranchs. But bycatch also occurs in purse seines, gillnets, shore seines and many forms of artisanal fisheries. The catch is usually dominated by small coastal species such as spadenose sharks and the scaly whiprays. Sometimes, neonate and juvenile scalloped hammerheads, common blacktips, bull sharks, eagle rays, and guitarfish are also caught in large numbers during the pupping months.

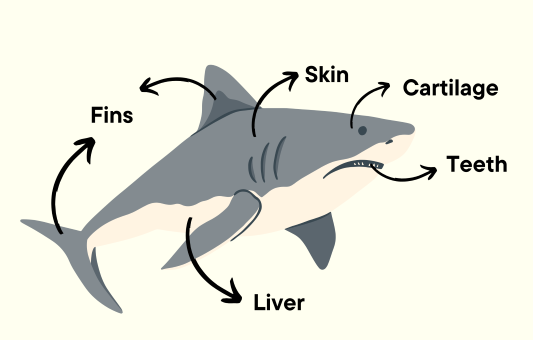

Demand for shark products

Artisanal fishers in India have been practising targeted shark fishing since the early 1900s. Recent trends indicate that fin trade remains a threat, but international demand for shark fins from Southeast Asia is declining. Now, the shark meat trade has a higher demand and value than the fin trade. Consumption was initially limited to economically disadvantaged communities. Over the years, the demand for shark meat has risen as it has become economically important. Restaurants in urban and tourist centres in Goa, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have been including shark meat products in their menus to meet the high demand from customers. However, a large chunk of the demand for shark meat has been linked to household consumption and restaurants without online menus. It has been found that it is the neonates and juvenile sharks that are under threat from the meat trade. There has also been an increase in demand for gill plates of manta and devil rays, even though their trade is regulated under Appendix II of CITES.

Climate change

Climate change may also be detrimental to sharks and rays. The warmer waters are affecting their migration patterns and behaviour, causing them to migrate to unexplored areas. Most of the shark species are apex predators, which means that changes in their movements might lead to altered ecosystems. Their prey is also experiencing similar movements, which would lead to the elasmobranchs returning to vacant feeding sites. Mangrove forests are vital nursery grounds and coral reefs are important habitats for elasmobranchs. In India, these habitats face threats due to urbanisation, aquaculture expansion, and climate change. Rapid coastal development destroys vital habitats, while shrimp farming encroaches upon these delicate ecosystems. Rising sea levels and extreme weather events exacerbate erosion and salinity intrusion, endangering the rich biodiversity and protective functions of these crucial coastal habitats.

Mislabelling of elasmobranch meat and lack of transparency

The meat of sharks and rays that is sold in local markets, restaurants, and through international trade, is often mislabelled. There is a lack of awareness about the various shark species that end up being served at restaurants. For example, quite a few threatened species are mislabelled and sold in place of the milk shark. Transparency in the shark and ray meat trade is pivotal for conservation. Mislabelling disguises the identity of species, thwarting efforts to monitor population declines and implement targeted protection. Accurate labelling through traceability mechanisms and DNA testing can deter illegal catches and trade of threatened species. When consumers, local markets, and international buyers are aware of the precise species they are purchasing, demand for vulnerable sharks decreases, incentivising sustainable practices. Enhanced transparency empowers authorities to enforce regulations effectively, supports science-based management, and safeguards biodiversity. By revealing the true impact of trade, transparency strengthens conservation efforts, promoting responsible fishing and contributing to the preservation of marine ecosystems.